After you’ve invested hundreds of thousands into your own ERP system, it’s clear you wouldn’t want to find out that there’s a much better alternative on the market. Fortunately, it is not easy for an SME to replace their ERP, and large clients hate it even more. But, the reputation of the ERP company is meaningful for new implementations, and for being able to add more value to their existing clients, by adding applications that either add new required capability, or solve a current problem.

The simple truth is that most ERP systems are necessary for running businesses, but they fail to yield the full expected value to all clients: to be in good control of the flow that generates the revenues.

I’m looking forward to your comments here or on my Linkedin post.

Fundamental Default Gap

When I encounter an ERP system for the first time, I first check whether it helps its user overcome Two Critical Challenges. With rare exceptions, a manufacturer who can’t handle these challenges is inherently fragile, where external factors determine the moment of a break.

All organizations have to make commitments to their clients. Part of such a commitment is the amount of the product or service to be supplied and its overall quality. Another important part is the time frame for the delivery. There are two broad possibilities for the time frame: either immediately whenever the client asks for it, or a promise for a specific date in the future.

This very generic description defines Two Critical Challenges:

- WHAT TO PROMISE: what can we promise our clients, while ensuring a good chance of meeting all commitments?

- HOW TO DELIVER WHAT WAS PROMISED: once we have committed to a client, how can we ensure fulfilling the delivery on time and in full?

It may seem that if you have a good answer to the first challenge, then the delivery is pretty much ensured. Well, consider Murphy’s law: “Anything that could go wrong will go wrong.” We are facing a lot of uncertainty, so following the plan is never just a straight walk, you need to deal with many things that go wrong, but that doesn’t mean that you cannot deliver as you’ve committed to. It just means you need to quickly identify problems and have the means to deal with them, still keeping the original commitment intact.

This article focuses on manufacturing companies, even though distribution companies face similar needs. Actually, most service companies also have similar issues with making commitments and then meeting all of them.

The potential value of any ERP package for manufacturing is to provide the necessary information, based on the actual data, to lead Operations to do what is required for delivering all sales-orders on time and in full, without generating too high cost. In other words: ERP should support the smooth and fast flow of goods, preferably throughout the whole supply chain, and at the very least, manage the flow from the immediate vendors to the immediate clients.

When properly modelled and used, the current ERP systems provide the production planners with easy access to all the data about every open manufacturing order and the level of stock of every SKU. The data also covers the processing and setup times for every work center, again when being properly input by the user. So, capacity calculations can be performed with current technology.

Question for ERP brands and developers:

How does that huge amount of data, currently collected by your ERP, help to overcome the Two Critical Challenges for your customers?

If this question sounds too rhetoric, I encourage manufacturers to share their experience on how they adapted to work around the gap after it was by default inherited with a chosen ERP package.

Manufacturing organizations seem to be very complex. While outlining the whole process from confirming a sale-order until delivery isn’t trivial, the ERP tools are good enough to handle that level of complexity. But synchronizing all the released manufacturing orders, which compete for capacity of resources, is a major problem. Consequently, even though timely delivery of one particular high priority order is not a problem, achieving an excellent score on OTIF (on-time, in full) seems very complicated.

So, in order to be able to answer the two challenges there is a need to have good control on the capacity of resources.

Promise, then deliver

Measuring capacity is not trivial. Just having to deal with setups adds considerable complexity. During the 90s, along with powerful computers with great ability to crunch millions of data items, the idea of creating an optimized schedule, taking into account all the open sales-orders, going through each order routing, considering the available capacity at the right time, came to life with a new wave of software called APS (advanced planning and scheduling systems). These systems were supposed to yield the perfect planning, meaning it could be performed in a straightforward way, accomplishing all the objectives of the plan. If this could really work, then the second challenge would have been solved as well.

However, the APS systems eventually failed. Some claim they could still be used for inquiring about what-if scenarios. Problem is: it can tell you what definitely wouldn’t work, for instance because of lack of capacity of just one resource. But APS failed to predict the safe achievement of all commitments, so its main value was, at most, quite limited.

The reason for the failure of all the APS is that on top of complexity of managing the capacity of many resources, there is considerable uncertainty, and any occurrence of a problem would mess up the optimal plan.

Relative to the APS programs, the development of ERP aimed at integrating many applications using the same database, without considering the capacity limitations and without striving for the ultimate optimal solution. Some ERP programs have widened the ability to model more and more complexity, others are still going with the basic structure.

Even when we have excellent data, and effective ERP tools, managing the uncertainty is quite a tough task. It is always tough – no matter the plant type or industry – because of the complexity of monitoring the progress of so many manufacturing orders. Every production manager struggles with the ongoing need to decide what work order has to be processed right now. This also means that processing other work orders is delayed. When the market demand fluctuates, when problems with the supply of materials occur, or when machine operators are absent, the production manager must have a very clear set of priorities, and certain flexibility with time, stock, and capacity to be able to respond immediately to any new problem. The objective is still valid: delivering everything according to the commitments to the client.

Note, if we come up with a solution to the second challenge (2. How to deliver what was promised), then we might also understand better what truly limits our offering (and commitment) to the market. Once we know that, we can come up with an effective planning scheme where every single promise made by our sales people is pretty safe.

This is where the insights of the Theory of Constraints (TOC) come to our rescue.

Key insight #1:

Only very few resources, usually just one, truly limit the output of the system.

The recognition of the above statement effectively simplifies monitoring the flow. In TOC we call that resource the ‘constraint.’ Certainly, the capacity of the constraint should be closely monitored. Several other resources should also be monitored, just to be sure that a sudden change in the product mix won’t move the ‘weakest link’ to another resource. The vast majority of the other resources have much less impact on the flow, as they have some excess capacity, which can be effectively used to fix situations when Murphy causes a local disruption.

One additional understanding from that key insight: the limited capacity of the constraint is what could effectively be used to predict the safe-time where the company can commit to deliver. More on it will be explained later.

Key insight #2:

An effective plan has to include buffers to protect the most important objectives of the plan.

Buffers could be time, stock, excess capacity, excess capabilities, or money.

In manufacturing we can distinguish between make-to-order (MTO) and make-to-stock (MTS). The vast majority of the manufacturing organizations produce both for order and for stock, sometimes within the same work-order there are quantities promised to be delivered at certain dates (MTO), while the production batch also includes items to cover future demand (MTS). This creates quite a lot of confusion, and makes the life of the production manager, who is required to locate all the parts that belong to a specific sales order, a never-ending nightmare.

You will be surprised but even the most popular ERP systems do not differentiate between MTO and MTS. If you wonder why obviously an MTS company manages its production the MTO way, check their ERP system default (and watch a follow-up video below for more explanation on this).

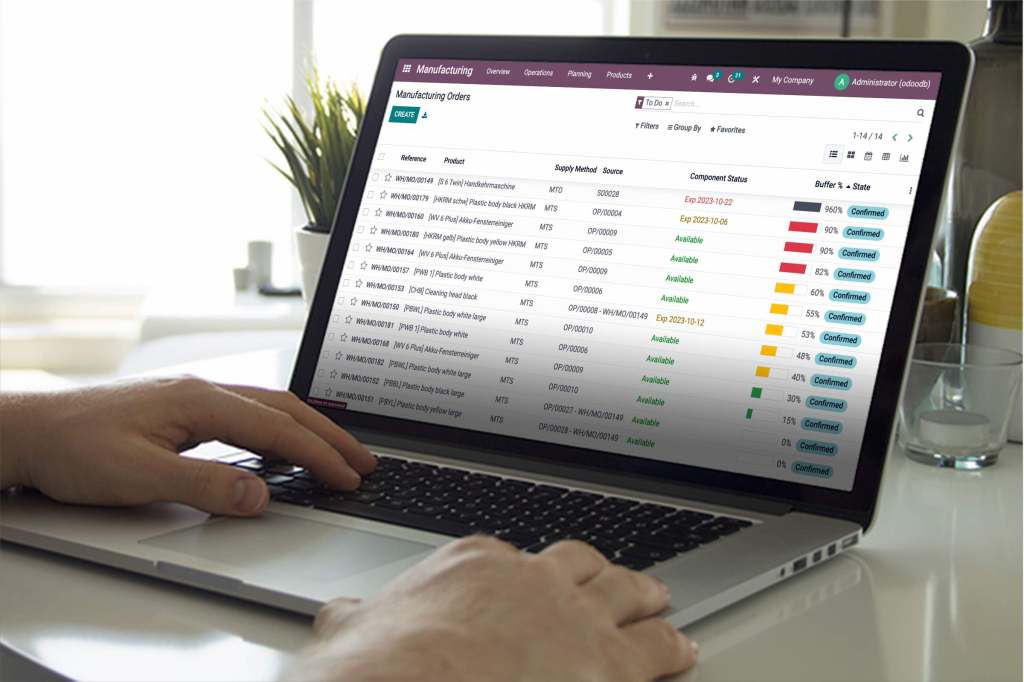

My team discovered one ERP system, Odoo, that distinctly differentiates between MTO and MTS. This distinction makes Odoo a strong contender for a platform on which to build the necessary features that address the key insights. I’m excited to see how effectively these features are already responding to two critical questions, and I look forward to discovering what more we can achieve in the future. Generally speaking, this capability is also possible with other ERP systems as well.

Every MTO order has a date that is a commitment. Considering the uncertainty there is a need to give Production enough time to overcome the various uncertain incidents along the way, including facing temporary peaks of load on non-constraints, quality problems, delays in the supply and many more. This means necessarily starting production enough time before the due date to be confident that the order will be completed on time. That time given to Production with a good confidence is called Time-Buffer, and in manufacturing it includes the net-processing time, because in the vast majority of manufacturing environments, the ratio of net-processing time to the actual Production Time is less than 10%. Thus, the order release date should be: due-date minus the time-buffer-days. We highly recommend not releasing MTO orders before that time, otherwise significant temporary peaks on non-constraints will be created.

Make-to-stock requires maintaining a stock buffer. The definition of the stock buffer includes on-hand plus open manufacturing orders for that item. Thus, when a sale automatically triggers the creation of a manufacturing order for the same SKU, then the stock buffer is kept intact.

Key insight #3:

The status of the buffers provides ONE clear priority scheme!

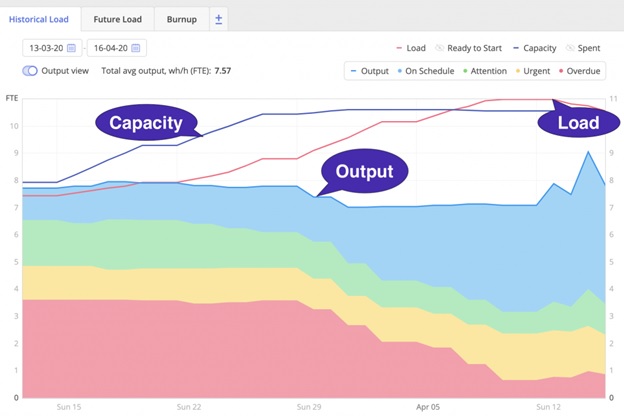

In TOC we call it Buffer Management. The idea is to define the status of the buffer as the percentage of how much of it is left. As already mentioned, in manufacturing the net processing time (touch time) of an order is a very small fraction of the actual production lead time. The most production time is spent waiting for the work-centers to finish previous orders. Thus, if a specific order becomes top priority, the wait time for that order would be significantly cut and so would the lead time.

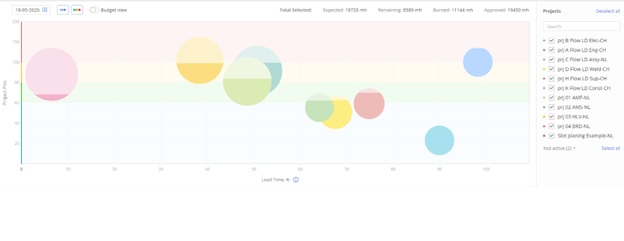

MTO orders use time buffers, while as explained earlier, MTS orders use stock buffers. Ideally, we should monitor both MTO and MTS orders in the same queue as you see in the Picture 1 below. When only one-third of the time-buffer or less is left until the delivery date, or the on-hand stock is only one-third or less of the stock buffer, the buffer status of that order is considered RED, meaning it has top priority. Once that red order gets the top priority the wait time is dramatically cut. The production manager facing a list of several red orders could decide to take expediting actions to ensure a fast flow of the red orders, so all of them will be completed by the due date.

For MTS orders the buffer status is the percentage of the on-hand stock relative to the stock-buffer, which also includes the WIP (work-in-process). Following the one priority scheme, using both stock and time buffers significantly improves the probability of excellent delivery performance. This happens mainly when some level of excess capacity exists, even on the constraint, and more so on the few other relatively highly loaded resources. However, when the demand goes up, then at some point in time the number of orders in RED increases sharply. When this situation happens, it radiates a clear warning: There is no way to meet the commitments as long as there is no significant increase in capacity. We can call this kind of warning “too much Red.”

Key Insight #4:

Monitoring the size and trend of the Planned-Load of the constraint, and few other highly loaded resources.

The Planned-Load of a specific critical resource is the total hours required to process all the confirmed sales-orders. This is done simply by going through all the backlog of orders and adding the required hours of work of that resource to process the orders. The most critical resource, the constraint, is expected to have the highest number of hours required for processing all the existing orders. The Planned-Load could be expressed as the date where we expect the critical resource to finish processing all the confirmed demand.

Note two critical advantages from the Planned-Load that benefit and align Production and Sales:

- We get an accurate prediction of the lead-time for a new order!

When a new order appears in the backlog, then in most cases it will be processed by the critical resource only after all the existing demand (confirmed orders) have been processed. When we add to the Planned-Load some extra time (usually half of the time buffer for that order), covering for the processing time of the constraint and going through all the rest of the routing, we get a safe-date we can commit to.

- Watching the trend of the Planned-Load provides us with signals on the overall trend of the market.

The Planned-Load should be re-calculated every day. The difference between today’s planned load and tomorrow’s is that the orders processed by the resource today disappear from the calculation, while new orders arriving today are added to it. When the Planned-Load of the constraint increases (see the right screen in Picture 2), it means more orders are coming than what the constraint has been able to process. If such a trend is consistent for some time, it might mean: a bottleneck is emerging. You either won’t be able to deliver on time (and suffer customer dissatisfaction), or you will be forced to increase the lead time (and consequently lose some business when your competition remains faster). When the trend goes down (as shown in the left screen in Picture 2), it means less orders are received from the market, and then it is possible to deliver faster.

Depending on the trend, the company should trigger a proper managerial initiative:

- either to increase the capacity of the constraint, possibly also the capacity of one or more of the other critical resources, as we don’t want them to become bottlenecks,

- or find ways to attract more orders and more new customers. Note, less loaded constraint means a shorter lead time. In markets where supplier response time and reliability matter a lot, a shorter lead time magnetizes new orders. This means if Sales and Operations activities are synchronized, any drop in demand could be just temporal.

Balancing carefully between demand and capacity

The combination of monitoring both the number of red orders and the Planned-Load yields a powerful piece of information on the stability of the organization, regarding the sensitive balance between demand and capacity. The advantage of Buffer Management is that it doesn’t depend on the quality of the vast majority of the ERP data, only on the consumption of time or stock. The advantage of the Planned-Load is its ability to issue a warning earlier than Buffer Management, giving the managers more time to react, including the option to add temporary capacity.

The actual value from the combination of Buffer Management and Planned-Load has been thoroughly checked using the MICSS simulator, developed by me during the 90s for testing various production policies and their impact on the business. When the market demand starts to grow, after some time the number of red orders suddenly increases. At that time the current delivery performance is still adequate. But after running the simulation for one or two more weeks, the disaster in the delivery is clearly seen. I hope and wish your factory’s reality is much better than that!

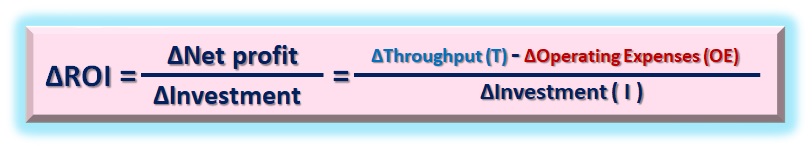

The four key insights could be effectively used to vastly improve the value and skyrocket ROI of any modern ERP system, still using most of the capabilities and algorithms of the original ERP.

My team and I at Enterprise Space, Inc. are determined to continue adding new algorithms and data visualisations to an ERP system that would focus the managers to the truly critical issues.

The next phase of value to the customers would be detailed by a subsequent article on how to support decisions when additional new sales initiatives are evaluated, predicting the net impact of those decisions on the bottom-line, taking revenues, cost and capacity into account, considering also the level of uncertainty.