It is natural to joke about consultants. A management consultant is an informal player in the power game within the organization, because he does not belong to the hierarchy. The consultant also does not take any responsibility and only rarely he has real-life experience as a manager.

There are two different types of management consultants. The first consists of those who see their role as facilitators that encourage people to express their views and help them to properly radiate them. These consultants shy away from expressing their own opinion on any subject matter. In this article I do NOT address this type of consultants.

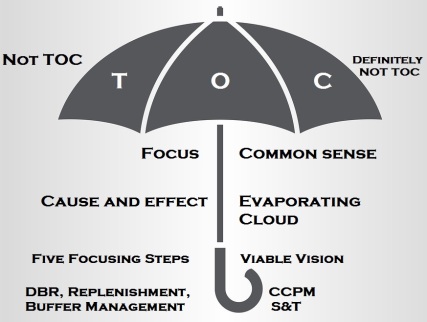

The other type of consultants clearly express very strong opinions. Most of those consultants make a thorough inquiry of the organization needs and then produce a document stating exactly what needs to be done. The big strategic consulting companies, like McKinsey, follow this approach. A different approach is where the consultant comes with certain ideas, but carries a dialogue with the client until a consensus is reached. I believe this is the way TOC consultants should follow.

Why do executives need consultants?

When the consultant is an expert in a very specialized area, like legal consultants or even marketing specialists, then the value is quite clear. While TOC is known mainly in Operations, the TOC BOK covers wide range of managerial areas, thus it cannot be considered specialized in a narrow field. In other words, TOC consultants help the executives of a company to do the job the executive is supposed to do! The emerging problem is that it creates an unfavourable image of an executive who is unable to do his job properly and the TOC consultant has to do it for him.

When the consultant brings new knowledge that cannot be easily gained then there is a certain justification for using him. Question is whether the organization should not expect their executives to be highly knowledgeable on all the areas under their responsibility. In other words, if TOC is not too specialized and yet it is relevant for the management of an organizational function – should not the executives be fluent in the relevant TOC knowledge?

This brings us to a critical conflict within TOC that started way back in the 80s. As I’m preparing myself to a webinar on the development of TOC this conflict is causing me considerable thinking:

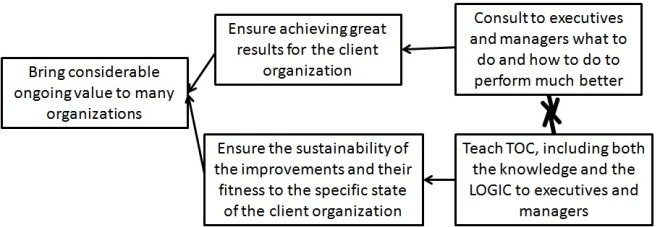

In the early days of the Goldratt Institute the idea was just to teach. The real problem was the inability of many clients to quickly implement the general solution advocated in the class, which had caused huge delays in the results leading people to distrust the methodology and coming back to the common flawed methods.

Switching to full consultation, directed at the top management, has achieved results much faster, but, it also showed the problem in keeping the drive to achieve even better results.

I think that the only way to resolve the conflict is to challenge the conflict itself by providing both educating and consulting, not necessarily at the same time, but eventually achieving both.

The focus on consulting also raised the already mentioned problem of the image of managers wasting money on external consultation to do what they need to do in the first place. The big consulting companies deal with that image by offering knowledge on the common practices in similar organizations to establish the “best practices.” The consultants are then viewed as bringing international experience on how recognized issues are dealt by others. So, the ruling assumption is that it is possible, and beneficial, to imitate what others do well and by this achieve results. This generates an explanation how come top executives invite international consulting companies to lead a change, based on benchmarking as a proof for excellence.

Personally I think that benchmarking leads to disastrous results, because they are derived by generic similarities, which do not fully match the map of cause-and-effect, especially the impact of certain unique characteristics that every organization has. On top of that I think that every organization has to build the way to success upon certain unique capabilities, which is quite contrary to benchmarking.

The answer to the image of wasting money to do what management has to do is that external consultants have the ability to bring perspective and ideas from outside the specific business area. The TOC training generates capabilities for identifying the essence of problems and the generic ways to overcome them. TOC is also tuned to identify flawed paradigms, for instance all those that stem from local perspective. This is an ability that even the top best executives cannot easily have, because most of their career they were in the same area and thus have adopted the same set of paradigms that only someone external can see the flaw. Note that when a paradigm that is shared by all competitors is proven invalid in certain aspects the opportunity from the updated paradigm is huge.

There is a related, still different, advantage for an external consultant. An executive, especially the CEO, is quite lonely in his/her hard decision making. Consulting anyone else within the organization has negative ramifications on the image of the executive within the organization. Consulting with an experienced clever consultant answers a basic need. We know that hard decisions mean that undesired outcomes might be caused. This is the nature of living in uncertainty with the various biases that we all carry with us. Discussing the benefits and the negative branches and then how to eliminate the negatives is a real need.

So, what are the requirements from an external TOC consultant to truly deliver value? The TOC formal knowledge can be effectively gained by courses and books. The ability to connect between generic insights, many of them challenge rooted paradigms, and the special characteristics of the organization require critical dialogue between the executives and the consultants. It is never “Do that and that – believe me it’d work”, it is hard thought processing that needs both the internal and the external minds to find the effective solution.

What if the consultant himself feels trapped between the generic ideas and the environment at hand? It should be a common occurrence because the translation of generic ideas to specific environments is never trivial. Think about the possibility of a consultant in a specific project discussing the matter with another consultant, who is not in touch with the specific environment. This is where I believe veterans like me can give value.