There are two types of assortments that differ by their basic message to the potential client:

- Whatever you truly need we have in stock or can produce it for you.

- We offer an attractive assortment for you to choose from.

Generally speaking the first one applies to products whose main value is a practical need. The clients are assumed to know a-priori their exact needs.

The second one, with the emphasis on ‘choice’, is for potential clients who enjoy browsing and is based on the value of ‘pleasure’. The reader is advised to read my post on The Categories of Value.

The difference in the type of value lends itself to different logistics. In the first type managing availability is critical to sales. A shortage means the right product for a specific client is missing, leaving the client either to choose the second best or go elsewhere.

The second type, which is fashion, books, music, art and similar products is focused on clients spending significant amount of time browsing, which already creates value for them. While sometimes clients might have a good idea what they look for (like the last book of Grisham), most of the clients enter the store wishing to be exposed to an assortment out of which they might choose one or more items.

This characteristic impacts the replenishment procedure. A sale of an item should invoke replenishment, but not necessarily of the same item. An assortment of fashion requires frequent changes. It seems logical that when a certain design generates high or stable demand, the same item should be replenished. However, when there is no evidence for special wide appeal of an item, then maybe it is a good idea to replenish the item with a different item?

I assume that creating an attractive assortment is an ‘art’, based on intuition and it is difficult to come up with clear guidelines. Most of the items within the same assortment have to appeal to a certain market segment in order to attract the browsing that eventually leads to sales. Sometimes one client even buys several items of an assortment just because he/she likes them and deciding upon only one is tough. This never happens in selling products for practical needs.

So, the choice of the items is a key for the success of an assortment. There should be a certain common taste through the whole assortment, but also providing variety to create pleasure during the browsing.

Another factor is the size of the assortment. How many similar, yet different, items can a store display as one assortment, which is effective in attracting potential clients?

An assortment of fashion goods might be too large. Browsing for too long might cause the client to give up. It is a known effect that too high variety attracts people to browse, but, actual sales are low. Certainly too small assortments definitely reduce sales.

How should we decide upon the size of an assortment?

The TOC generic directive is to start with a guess and then check signals whether the initial assessment is too large or too small. Such a signal can be the rate of clients entering the store that go to the specific assortment. Another is how much time on average is spent there. When the time is short, it might signal disappointment, which could be due to general taste or that the assortment is too small. Very long average time indicates too large assortment, which could be validated by checking the ratio of sales to the number of clients browsing. All that information has to be collected. Sporadic observations in a week could provide good enough signals whether to re-evaluate the size and content of the assortment.

The distribution of sales of different items within the assortment is another signal, but it is not straight-forward. When the tail of the distribution, the sales of the slow-movers, is pretty long then a possible cause is that the assortment is too large. However, providing variety is an important factor for attracting clients even when most clients eventually choose only few specific items. Different types of assortments might have different lengths of effective tails which are required for the pleasure of browsing. Testing the effectiveness by carefully dropping several slow-movers and realize the resulting impact on sales of the whole assortment is absolutely necessary.

Managing assortments is linked to managing availability and creates several challenging dilemmas. Many products/designs are offered in several sizes. As long as the design is to be kept as a part of the assortment, we should keep availability of all sizes. However, when there is a decision to discontinue that design, then the whole design should NOT be replenished. It opens the question what to do with the remaining items of that design? My own recommendation is to carry the remaining items to another spot and sell it cheaply, without any commitment to availability.

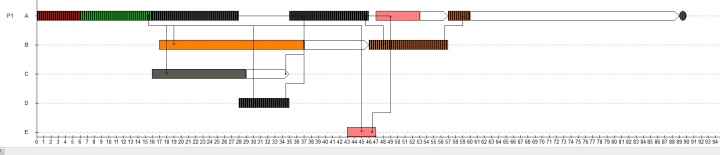

The idea of maintaining a certain size of the assortment means that when you add a new design you take out an existing one and vice-versa, when a specific design is taken out there has to be a new design ready to move in. This means having to manage a buffer of new designs waiting for an opportunity to enter the assortment at a specific store. These buffers have to be managed through buffer-management to ensure there are never shortages of new designs, and there are never too many new designs waiting for the opportunity to be displayed and sold at a store.

The more generic point is the need to find practical and effective ways to combine human intuition with systematic analysis supported by software. I have seen that need, combining intuition and hard analysis, when I developed the decision-support the TOC Way (DSTOC) as an expansion of Throughput Accounting. As you can see the need to combine intuition with logical systematic analysis does not stop there.