Strategy, with a capital S, is a plan to achieve the goal. Too many organizations do not have any plan for the future. Some try hard to survive; others are simply stagnated, serving the same group of customers with the same products and with very little initiated changes. Other organizations have very ambitious vision and mission, but they don’t take them seriously.

What could be more important for an organization, any organization, than to plan how to achieve more of the goal? How come so many organizations are stuck with their current situation to the point that ideas about the future look to them irrelevant?

Fear of losing what we already have plays a big part in being reluctant to look for new initiatives that could make a difference. The compromised solution is to imitate the competitors. You see this behavior in the banking and airline sectors where the copying capabilities are highly developed.

This imitation behavior keeps the organization within the comfort zone of the accepted norms of the specific sector. One risk is that a “crazy” competitor would challenge a basic norm, making it difficult to copy, and get a lead in the market. Southwest Airlines did that to the big airlines and opened a new trend of low-cost carriers.

Going out of the inertia is better provided by collaborating with people outside the specific comfort zone, letting them ask silly questions and irrelevant suggestions, looking for the one that would stir the question “why not?”

Strategy dictates a certain flow-of-initiatives. The flow-of-initiatives in an organization is always internally constrained by management-attention. Exploiting this ultimate constraint is through FOCUSING on the few most promising future initiatives. Thus, we should look for one key element that, once achieved, would bring the organization to a new level of performance. Any key element requires a group of different initiatives to make it work. The necessary characteristics of this key element have to be:

- It vastly enhances sales, allows charging higher price or vastly reduces the cost

- Delivering new value to large enough market segment(s) is the most effective direction and it impacts both the quantity to be sold and the ability to charge more

- Whatever is the key element – it should not be easy for competitors to imitate

- The key element has to be based on a unique capability of the organization

- Otherwise it is easy to imitate

- The unique capability could be learning or acquiring new capabilities

- The risk, associated with the proposed change, is small, or can be carefully tested in a way that would not cause big damage

Such a key element of Strategy was called by Goldratt: a decisive competitive edge (DCE), as this is what it targets to achieve. Note that if the organization truly achieves a DCE then the level of overall risk goes down! The risky part is to ensure that the DCE is truly effective.

Note, gaining a DCE does NOT mean dominating a whole market! It means being superior in a certain market segment(s). Still, competitors might dominate other market-segments due to superiority in another need of the market.

Few organizations have a clear DCE. However, these organizations are well known, creating the impression that many organizations have such a DCE. Just to quote some clear examples: Apple, Google, Toyota, Mercedes, Lonely-Planet and Zara.

Very large organizations have a natural DCE from being big: their products look like a “safe purchase” (you cannot go wrong with SAP, IBM or LG). Thus, it is the duty of the smaller organizations to come up with an idea for a specific DCE and by that “steal” part of the market from the big ones.

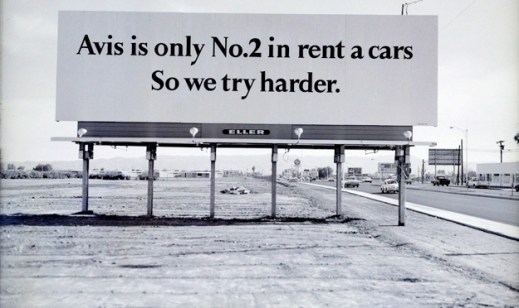

Avis got a lot of attention by the slogan “We are number 2, we try harder.” It promises more value to the customers through better service. This promise divided the market segments into two: those who preferred no. 1 because it seemed safer, and those who liked to be treated well. Avis’ DCE targeted the ‘better treatment’ market segment.

Dr. Eli Goldratt came up with several potential DCEs based on the TOC knowledge as a unique capability. Committing to availability is one option in certain cases, rapid-response is another. It is a huge mistake to assume that these are the only options for gaining a real DCE.

I claim it is the duty of top management of every single organization to come up with a DCE. What could be safer for the future of an organization other than a well-established DCE?

How should organizations come up with a DCE?

- Recognize it as the responsibility of top management

- Examine the capabilities of the organization, including learning new capabilities

- Identify a need, or a wish, of many potential clients that can be delivered by the organization

- Note, the need defines a market segment for which the need is important

- Make sure it would not be immediately copied

- Develop the ways to radiate the full value to the potential clients

- Carefully plan and execute whatever is required to deliver the extra value to the clients

- Test the idea first and put signals to warn whenever the minimal expectations are not met

More posts would be dedicated to Strategy, covering the range from checking the power of the DCE to planning the transition to identifying potential threats early enough.

Would you like to discuss potential ideas for DCEs?

Excellent post. Thanks Eli

LikeLike

I would love to discuss DCEs!

I’m working on one now for a distributor in a marketplace for used parts. Like all parts, I think, some are fast moving and some sell very slowly, depending on the rate at which they wear. All these parts can be bought new from the OEM but even the OEMs don’t always have availability of the fastest moving ones! Used parts sell for between 90% and 10% of OEM list prices.

The situation of the industry is that no used part provider is able to offer full availability. The consumers and resellers of the parts are perpetually seeking the fast runners; all that become available are immediately sold. In seeking an competitive edge conventionally, the best a reseller can do is have a higher proportion of the desired parts. Most of the companies that try to offer availability end up with higher inventory, which puts pressure on what prices they can offer and earn an attractive return on investment. This results is a powerful buy-low, sell-high bias.

My current direction for a solution is to capitalize on the prevailing desires by buying-high and selling-low, if doing so accelerates the flow of goods. However, selling low both violates your guideline above but is a means to purging most inventories.

LikeLike

Henry, do you strive to achieve an DCE based on low price? It could work only if your flow is grossly accelerate AND you still provide excellent availability. You buy for relatively high price, because you like to ensure that every purchase order to the OEM is answered quickly, and you charge relatively low (I assume still higher than what you paid) to attract higher quantity. This means very low T per unit. You need a lot of quantity to sell to generate enough T to cover not just your OE, but also the investment in inventory. I’m not sure the demand will go up that much. When a part is missing the price of the part is not all that critical.

Why not base your DCE on having better availability than the competition? You might need to pay the OEM higher price to ensure fast response. But, why not to charge more the customer who needs the part NOW?

If you can achieve good response, rather than availability, by making agreements with your competitors that when you are out of a part they have – they ship the part to the client, then you gain the DCE of becoming the one calling point. In such an environment a certain collaboration-competition is a win-win, and it is much better than you charge low.

By the way, such relationships exist between the airlines. They move passengers to the competitors when needed (overbooking or cancellation of flights).

LikeLike

Let’s say we are a junkyard that buys automobiles and sells them in three ways.

1) We resell the whole car quickly to somebody who wants to drive it, usually something will need to be repaired first by the buyer.

2) We sell the major components: engine, transmission and body to someone who wants to make a usable car.

3) We break the car down into its component parts and sell the parts.

The situation of junkyards is that it usually doesn’t pay to buy a whole car just to get some fast selling engine part; the result would be even more slow selling parts out in the yard. Likewise, there is negative margin potential to buy a requested part from the OEM. We don’t command a discount; the OEMs wish we didn’t exist at all so there would more demand for their new parts.

The junkyard marketplace has these dynamics:

* The average price paid for a car is $1,000. The parts for the car will eventually sell for $2,500 but that takes 5 years on average.

* On average, the $2,500 of price is recovered like this:

– $500 in one month

– $500 in months 2-6

– $500 in months 7-18

– $500 in months 19-36

– $500 in months 37-60

* Because there is no way to determine the TVC of a given part, “lot costing” is used. Every time a part is sold from a car, some proportion of the selling price is deducted from the cost paid for that car.

* Because the company prefers to delay paying taxes on its profits, it arbitrarily assumes that the TVC of parts it sells are 80% of the selling price of the part, until such time as all the cost basis of the car is reduced to $0. After that point, 100% of the sales that come from parts of that car is Throughput. (Expected T% of a car is ($2,500 – $1,000) / $2,500 = 60% but there is wide variation from car to car and many parts are never sold.)

Because of the above factors, management recognizes that they do not know their inventory turns. Consequently, they pay attention to their cash to cash cycle. When they have $1,000 on hand plus what they think is a safe cushion, they buy a car.

In such a world, nobody can offer full availability without very high inventories. Since there is a full price option out there (the OEMs) and aftermarket suppliers of lower priced new parts, there is no great premium to be gained from having full availability of used parts. Therefore, buying another car every time a high velocity part is needed unnecessarily increases I without enough of an increase in T to make it worthwhile.

LikeLike

Henry, your original comment referred to a distributor for used parts. It makes sense to me to have such a distributor, or a supermarket for parts, which buys from the junkyards. I also thought that the distributor also holds new parts, which also makes good business sense to me.

OK, let’s refer now to the junkyards situation.

First, I claim that selling used-parts that are obtained from buying cars the whole revenue is throughput! In other words – there is NO TVC! The expense of the car is ‘I’ and it turns to be periodically OE. I can give more explanations why I claim it, but this is a side issue of our discussion.

Of course, for tax purposes what is legally allowed, and worthwhile economically, should be used. But, I don’t need to use the same tax rules for running regular decisions of my business.

I assume your question is: what DCE could such a junkyard achieve? It cannot offer availability. So, what is left is to compete on price, get faster flow, which would improve availability. This improvement is very small because the junkyard does not necessary buy the same car model with the free cash.

I think that having a link between the junkyards and the clients would partially solve the problem. If that distributor or supermarket for used-parts also complete the offering with new parts, then the level of availability looks to me as a DCE relative to the option to contact many junkyards to find a used-part for cheaper price. Consider also the case that a whole list of parts is required and how long could the garage spend to call junkyards to find out what is available.

What can we do if there is no such additional link in the supply chain?

I still believe that a junkyard that is ready offer limited collaboration with the other junkyards, and by this create a virtual large-shop, gains a DCE for himself, while the others win as well but not to the same degree. The idea is that any request the junkyard gets it is the responsibility of the junkyard to find it somewhere. When he find it in another junkyard – the sale for that part goes to the other junkyard. If not used-part can be found then a new one is bought – all is done by the junkyard.

Is such a collaboration against the trust-laws? You tell me as I don’t know. Note, the collaborators do not match their pricing – just agree to supply to the end client upon request. Isn’t it basically the way Amazon do?

I’d also suggest the junkyard to be able to buy new parts to complement the inventory. The OEM may hate the junkyard, but refusing to sell to them would not remove the junkyard out of the market. So, they need to live with the “enemies”. Having other aftermarket producers make it even more necessary for one to offer better availability than anybody else and for a variety of car models.

As a fun story, my regular cab driver to and from the airport is a similar story. All he owns is his one taxi and he is not part of any station or group. But, he has established collaboration of other taxi drivers like himself to create such a virtual taxi-station. So, I as a client who prefers to go to the airport and back with a cab, rather tan leave my car at the airport, find a very reliable service. I can safely call it a DCE, because it is not just a taxi-station, it is a person you know you can trust.

My main point is: many ideas for a DCE are already in place and you have seen it. But, they are implemented in a different business area. Translating ideas from business to business is possible and beneficial if you know to analyze the main ingredients of the value to the customer and the operational way to deliver that value.

I like to hear what you think Henry.

LikeLike

One thing that I think, Eli, is that you are brilliant! I love your analysis.

First, I particularly like the idea of treating any sale as Throughput. I have already specified that the dollars in our IDD calculation should be dollars of estimated reasonable resale price. Otherwise, our inventory metric would no longer apply pressure on us to move the slow sellers, after the early sales (assuming costs are 80% of resale, in this case) reduce the lot cost to $0. I want the slow sellers liquidated into cash, which we can use to buy another car sooner. The risk avoided by your suggestion of considering Sales = Throughput is that our people might confuse the “story” we tell our government and financial reality of our situation. However, we still need to decide on the logic of how much “I” to write off in our Throughput Accounting books and when to expense it.

With respect to the “supermarket” link that provides availability, I hadn’t thought of that. It is a particularly interesting idea. There are a few existing big companies that try to do this. They do command discounts from the OEMs so they can sell with positive T.

My direction for a solution was an “inventory turns” model masquerading as a just another junkyard, which is why I initially termed the company as a “distributor.” As I envisioned it, the company’s internal advantage would be turns over margin. As you mentioned, a faster flow of cars would tend to make more parts available. We could sell to other junkyards and to repair shops as well. My idea was to always be working to have no inventory.

Justin Roff-Marsh has suggested thinking of our “I” in terms of 3 categories: Steam, Water and Ice. Steam represents the fast movers, which dissipate on their own. Water, evaporates slowly – parts that will move at attractive prices. The Ice represents parts that will either become dead inventory or sell eventually. Justin further suggested treating the Water as if it was on a conveyor belt of a fixed length. These parts can be marketed and sold for only a fixed amount of time and then it is declared to be Ice and disposed of at any price. Under this model, there is only momentary Steam and Ice. Practically, all of the inventory is Water and that has a short, say months long holding period. With respect to whole cars, we treat them like Steam, and if they don’t readily flip whole, we tear them down, following the guidelines above in this paragraph.

In any given batch of parts from one vehicle, some of the typical Water (attractive but not immediately in demand) parts will not sell during their designated ride down the conveyor and fall off into the Ice bin (junk pile). However, in with the junk, will be some attractive parts that were expected to sell quickly at respectable prices but just didn’t in this particular time frame. If these designated Ice parts are sold as a bundle, the good ones will provide a value reference for the junk. In other words, a buyer will say, “Oh, I can sell this and that for $1,000 pretty soon. So, I’ll offer $1,000 for the whole lot and make my profit on the remaining parts, even though I know they won’t all sell.

LikeLike