Strategy, with a capital S, is a plan to achieve the goal. Too many organizations do not have any plan for the future. Some try hard to survive; others are simply stagnated, serving the same group of customers with the same products and with very little initiated changes. Other organizations have very ambitious vision and mission, but they don’t take them seriously.

What could be more important for an organization, any organization, than to plan how to achieve more of the goal? How come so many organizations are stuck with their current situation to the point that ideas about the future look to them irrelevant?

Fear of losing what we already have plays a big part in being reluctant to look for new initiatives that could make a difference. The compromised solution is to imitate the competitors. You see this behavior in the banking and airline sectors where the copying capabilities are highly developed.

This imitation behavior keeps the organization within the comfort zone of the accepted norms of the specific sector. One risk is that a “crazy” competitor would challenge a basic norm, making it difficult to copy, and get a lead in the market. Southwest Airlines did that to the big airlines and opened a new trend of low-cost carriers.

Going out of the inertia is better provided by collaborating with people outside the specific comfort zone, letting them ask silly questions and irrelevant suggestions, looking for the one that would stir the question “why not?”

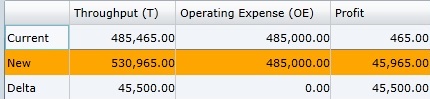

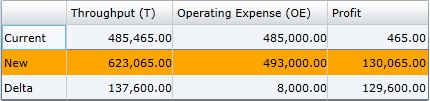

Strategy dictates a certain flow-of-initiatives. The flow-of-initiatives in an organization is always internally constrained by management-attention. Exploiting this ultimate constraint is through FOCUSING on the few most promising future initiatives. Thus, we should look for one key element that, once achieved, would bring the organization to a new level of performance. Any key element requires a group of different initiatives to make it work. The necessary characteristics of this key element have to be:

- It vastly enhances sales, allows charging higher price or vastly reduces the cost

- Delivering new value to large enough market segment(s) is the most effective direction and it impacts both the quantity to be sold and the ability to charge more

- Whatever is the key element – it should not be easy for competitors to imitate

- The key element has to be based on a unique capability of the organization

- Otherwise it is easy to imitate

- The unique capability could be learning or acquiring new capabilities

- The risk, associated with the proposed change, is small, or can be carefully tested in a way that would not cause big damage

Such a key element of Strategy was called by Goldratt: a decisive competitive edge (DCE), as this is what it targets to achieve. Note that if the organization truly achieves a DCE then the level of overall risk goes down! The risky part is to ensure that the DCE is truly effective.

Note, gaining a DCE does NOT mean dominating a whole market! It means being superior in a certain market segment(s). Still, competitors might dominate other market-segments due to superiority in another need of the market.

Few organizations have a clear DCE. However, these organizations are well known, creating the impression that many organizations have such a DCE. Just to quote some clear examples: Apple, Google, Toyota, Mercedes, Lonely-Planet and Zara.

Very large organizations have a natural DCE from being big: their products look like a “safe purchase” (you cannot go wrong with SAP, IBM or LG). Thus, it is the duty of the smaller organizations to come up with an idea for a specific DCE and by that “steal” part of the market from the big ones.

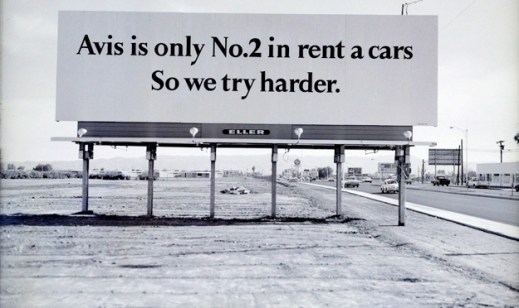

Avis got a lot of attention by the slogan “We are number 2, we try harder.” It promises more value to the customers through better service. This promise divided the market segments into two: those who preferred no. 1 because it seemed safer, and those who liked to be treated well. Avis’ DCE targeted the ‘better treatment’ market segment.

Dr. Eli Goldratt came up with several potential DCEs based on the TOC knowledge as a unique capability. Committing to availability is one option in certain cases, rapid-response is another. It is a huge mistake to assume that these are the only options for gaining a real DCE.

I claim it is the duty of top management of every single organization to come up with a DCE. What could be safer for the future of an organization other than a well-established DCE?

How should organizations come up with a DCE?

- Recognize it as the responsibility of top management

- Examine the capabilities of the organization, including learning new capabilities

- Identify a need, or a wish, of many potential clients that can be delivered by the organization

- Note, the need defines a market segment for which the need is important

- Make sure it would not be immediately copied

- Develop the ways to radiate the full value to the potential clients

- Carefully plan and execute whatever is required to deliver the extra value to the clients

- Test the idea first and put signals to warn whenever the minimal expectations are not met

More posts would be dedicated to Strategy, covering the range from checking the power of the DCE to planning the transition to identifying potential threats early enough.

Would you like to discuss potential ideas for DCEs?